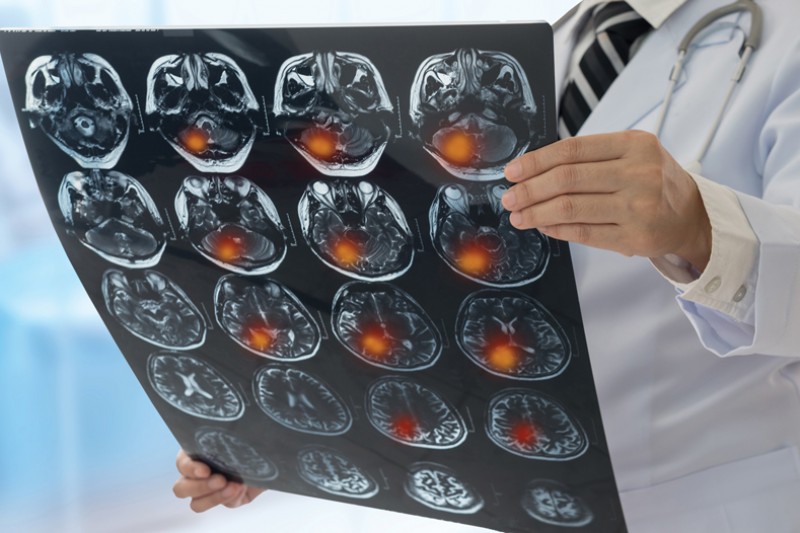

At least 100,000 people in the UK have a stroke each year and around a third of them are of working age. In 1990 only a quarter of strokes were experienced by people aged between 20-64 years old, meaning that the average age of stroke victims is falling. BU’s Dr Kathryn Collins, a Lecturer in Physiotherapy, noticed this trend emerging while working as a physiotherapist in Chicago and while undertaking her PhD at the University of East Anglia.

“My PhD explored neural plasticity, and the corticospinal tract which connects our brain to different muscle groups. I was really interested in the way our brains can change: whether from learning a new skill or from being damaged through a stroke,” explains Dr Collins, “For example, in someone who has had a stroke, we might see an undamaged area of the brain developing differently in order to compensate for an area that has been damaged.

“Through both my practice and my research, I noticed that my patients were becoming much younger. Not only were this group trying to recover from their strokes, they were also trying to get back to work. Working gave them a purpose as well as enabling them to provide for themselves and their families.”

There are a number of reasons why people are at risk of having a stroke at a younger age. Some may be more susceptible to blood clotting because of a pre-existing condition, such as sickle cell anaemia, while others may be at risk because of certain lifestyle factors. These could include stress, poor diet or lack of physical activity.

Now at Bournemouth University, Dr Collins has been continuing her research into the facilitators and barriers to returning to work. Her research was funded by BU’s Acceleration of Research & Networking (ACORN) grant scheme, which provides promising Early Career Researchers with the opportunity to lead and manage their own research project.

“The funding enabled me to carry out a systematic review with two of our physiotherapy students. It was a really good opportunity for them to get involved in research and for them to broaden their skills. Through this review, we have been exploring hidden impairments which were seen as a significant barrier to returning work.”

Dr Kathryn Collins

Lecturer in Physiotherapy

Through both my practice and my research, I noticed that my patients were becoming much younger. Not only were this group trying to recover from their strokes, they were also trying to get back to work.

Dr Collins also worked with BU’s Public Involvement in Education and Research (PIER) Partnership to run a number of focus groups with stroke survivors. The PIER Partnership put her in touch with the local Stroke Association, who were keen to be involved. Through these focus groups Dr Collins was able to identify a number of barriers and facilitators to returning to work.

“Peer support was big factor in helping people back to work, as it gave stroke survivors the opportunity to learn from someone else who had been in the same position,” says Dr Collins. “Learning to listen to their bodies was also important. If they felt fatigued, for example, then they needed to learn that it was OK to take a break and rest.

“Workplace support made a big difference too. Being offered a phased return to work, having a flexible working pattern or having adjustments to help them carry out tasks they now found difficult were all examples of the kinds of support people found beneficial.”

In addition to this, training, longer rehabilitation, family support and returning to or learning new hobbies were seen as facilitators to help people return to work. The latter often helped to increase confidence which would then spill over into other areas of life“One of the biggest barriers to returning to work were hidden impairments, such as emotions. People experience a huge range of emotions after a stroke; anxiety about having another stroke, frustration at not being able to do things they could do before or guilt that they were no longer able to support their families in the same way. These emotions could then lead to changes in their behaviour or their personalities,” explains Dr Collins.

“Fatigue was also a significant barrier. Some people had returned to work, only to have to give it up altogether shortly afterwards as they hadn’t realised how fatigued they would be. In addition to this, some stroke survivors might face physical barriers such as finding it difficult to drive, climb stairs or get out of their chair easily.”

Changes in cognition were also recognised as a barrier. Some stroke survivors reported no longer being able to process information in the same way, finding that they felt overwhelmed or were facing ‘information overload’ if faced with too much to process at once.

“The final set of barriers centred on perceptions; both of their employers and colleagues. Some people found that there was a lack of understanding about the effects of a stroke, which meant they didn’t have the right support at work. It was felt that employers were better at making adaptations for people with visible, physical disabilities, but less so for people who might have hidden impairments.”

As the project draws to a close, Dr Collins is now considering what her next steps will be and how she can ensure that her research findings can make a difference to stroke survivors.

“I’d like to broaden my research to speak to more stroke survivors to make sure that I’ve correctly identified all the barriers and facilitators to returning to work. I’d also like to speak to employers to find out what their perceptions are,” says Dr Collins. “Ultimately, I want to be able to use my research findings to inform the support that physiotherapists and other health professionals provide to stroke survivors. My goal is to make sure that we’re providing the right kind of support and interventions to enable stroke survivors to get the most out of their lives.”

Dr Collins with colleagues

Dr Collins with colleagues