Using WHO, US Bureau of Statistics and World Bank data, we analysed Britain’s economic input into healthcare – its GDP Expenditure on Health (GDPEH) – and compared it to 20 other Western countries, to show how effective and efficient the NHS really is.

Successive UK governments have waxed lyrical about the importance of the NHS. But they haven’t put their money where their mouths are. Britain actually spends relatively little on health, suggesting it is of a lower priority than most governments suggest. In 2013, the UK’s GDPEH was 9.1%, placing it equal 17th out of the other 21 Western countries. Western European averaged 10.3%, Germany 11.3%, France 11.6% and the US 17.1%. This means that for every £100 the UK spent on healthcare, the financially prudent Germans spent £124.

The UK’s chronic underfunding of health becomes even more pronounced over time. Over the last 30 years, Britain’s average GDPEH is just 6.9%, the lowest of all the Western nations we compared it to. France and Germany, by comparison, spent an average of 9.4%, or £136 for every £100 spent by the UK.

While every country we monitored increased their GDP expenditure on health over time, Britain’s GDPEH fell in the years 1984, 1985 and 1987 under Thatcher; in 1984 and 1997 under John Major’s premiership; and in 2011 and 2013, under the coalition government of David Cameron, dropping from its highest level of 9.4% in 2010 down to 9.1% in 2013.

As people live longer, every Western country faces growing demands on its health services. Yet Britain’s funding of healthcare continues to be below the Western European average.

Value for money?

So what has happened? Secretary of State for Health Jeremy Hunt’s sound-bite promise of a 24/7 NHS was accompanied by a proportional cut in funding. The plug has been pulled on bursaries for university nursing students, and the government has complained that the NHS spends too much on agency nurses. And yet, as the figures above show, compared to other nations, Britain already gets the NHS on the comparative cheap.

But what about clinical outcomes? Do Britons suffer as a result? We hear so many scare stories in some mainstream media, not least the Mid-Staffordshire scandal of “unecessary” deaths. Yet over the past 20 years, my research shows that the UK has enjoyed the second biggest reduction among the 21 nations of total adult deaths in those aged 55-74, down 48%. This compares to 36% in the US and significantly less than 17 other countries.

Britain also had the sixth-equal biggest fall in cancer mortality, down 28% and significantly better than 14 countries over the period. Indeed, compare these numbers with its relatively low GDPEH spend, and the UK’s health system is the second most cost-effective in the world.

But not all is well with the NHS. For example, while every nation reduced its child mortality (those aged up to four) between 1990-2013, my research shows that the UK’s rate fell by 42%, a decent drop but a smaller reduction than that seen among adults. Nine countries also had significantly bigger reductions in child mortality than Britain. If the UK had seen the same reduction over the period as Portugal – which used to have the highest rate in the West but has since seen dramatic improvements – on average in this century there would have been 1,042 fewer grieving parents every year.

But is this the fault of the NHS? Not really. Britain also ranks third highest in relative poverty among Western nations. So along with having one of the lowest funded health systems, British children can also be considered comparatively “disadvantaged”, with all the health problems that can entail.

Hunt often quotes the Francis Report into Mid Staffs but tends to ignore the paragraphs related to resources, which state that there was “a mismatch between the resources … and needs of the services … without protest or warning … they failed … because of the … the system around them”.

The NHS can only be judged by comparing it with other countries. It achieves proportionately more with relatively less and for that it should be applauded. But as more is demanded of it, it will fail. Britain as a whole needs to appreciate that it gets the NHS on the comparative cheap – and demand that the government at least matches the spending of the other Western nations, or risk losing it forever.

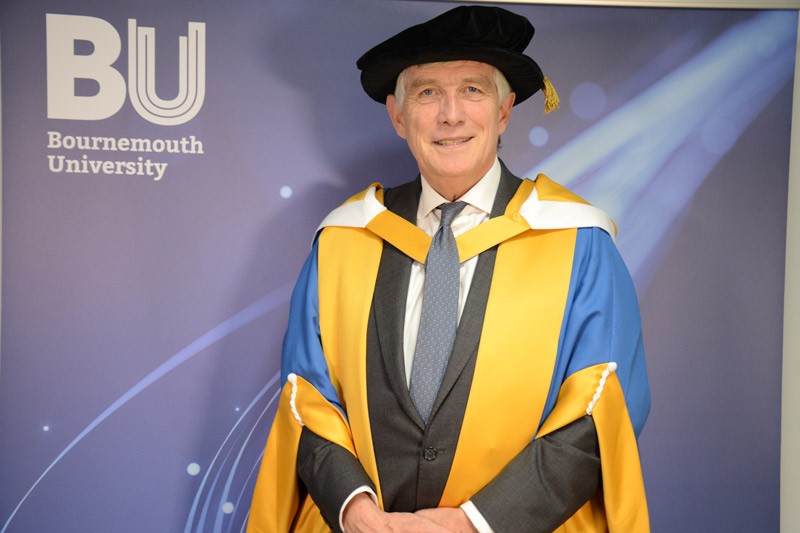

Colin Pritchard, Professor of Psychiatric Social Work, Bournemouth University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.