Expanding marine protected areas by 5% could boost fish yields by 20% – but there's a catch

Sweetlips shoal in the Raja Ampat marine protected area, Indonesia. SergeUWPhoto/Shutterstock

Sweetlips shoal in the Raja Ampat marine protected area, Indonesia. SergeUWPhoto/Shutterstock

Peter JS Jones, UCL and Rick Stafford, Bournemouth University

Marine protected areas, or MPAs as they’re more commonly called, are very simple. Areas of the sea are set aside where certain activities – usually fishing – are banned or restricted. Ideally, these MPAs might be placed around particularly vibrant habitats that support lots of different species, like seagrass beds or coral reefs. By preventing fishing gear such as towed seabed trawls from sweeping through these environments, the hope is that marine life will be allowed to recover.

When used well, they can be very effective. MPAs have been shown to increase the diversity of species and habitats, and even produce bigger fish within their bounds. A new study argues that by expanding the world’s MPAs by just 5%, we could boost future fish catches by at least 20%. This could generate an extra nine to 12 million tonnes of seafood per year, worth between USD$15-19 billion. It would also significantly increase how much nutritious fish protein is available for a growing human population to eat.

So what’s the catch?

Spillover versus blowback

The scientific rationale is sound. We already know that MPAs can increase the numbers of fish living inside them, which grow to be bigger and lay more eggs. The larvae that hatch can help seed fish populations in the wider ocean as they drift outside the MPA, leading to bigger catches in the areas where fishing is still permitted. We know fish can swim large distances as adults too. While some find protection and breed inside MPAs, others will move into less crowded waters outside where they can then be caught. Together, these effects are known as the spillover benefits of MPAs.

The study is the first to predict, through mathematical modelling, that a modest increase in the size of the world’s MPAs could swell global seafood yields as a result of this spillover. But while the predictions sound good, we have to understand what pulling this off would entail.

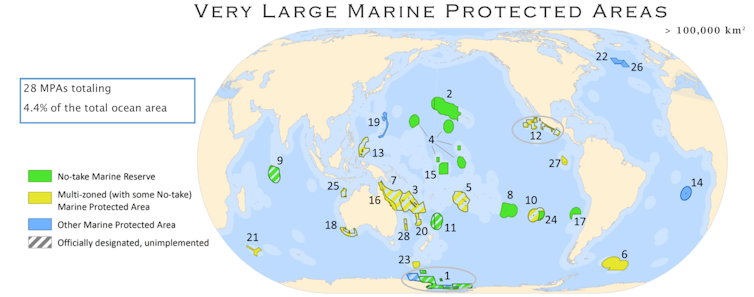

The study maintains that the new MPAs would need to be carefully located to protect areas that are particularly productive. Locating MPAs in remote areas offshore, which are hard to access and typically unproductive, would have much smaller benefits for marine life than smaller, inshore MPAs that local fishing vessels can reach. Just 20 large sites in the remote open ocean account for the majority of the world’s MPAs. As the low hanging fruit of marine conservation, these MPAs are often placed where little fishing has occurred.

A minority of the world’s MPAs are strict no-take zones. Marine Conservation Institute/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

A minority of the world’s MPAs are strict no-take zones. Marine Conservation Institute/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

The MPAs themselves would also need to be highly protected, meaning no fishing. Only 2.4% of the world’s ocean area has this status. Increasing this by a further 5% would mean roughly trebling the coverage of highly protected MPAs, and that’s likely to provoke a great deal of resistance. Many fishers are sceptical that spillover can boost catches enough to compensate for losing the right to fish within MPAs and tend to oppose proposals to designate more of them.

People in the UK are often surprised to learn that fishing is allowed in most of the country’s MPAs. While 36% of the waters around the UK are covered by them, only 0.0024% ban fishing outright. Increasing the number and size of highly protected MPAs from just these four small sites to 5% of the UK’s sea area would represent more than a 2,000-fold increase. This would be strongly resisted by the fishing industry, snatching the wind from the sails of any political effort ambitious enough to attempt it.

Keeping fishers on board

Gaining the support of local fishers is crucial for ensuring fishing restrictions are successful. That support depends on fishers being able to influence decisions about MPAs, including where they’ll be located and what the degree of protection will be. Assuming that designing highly protected MPA networks is mostly a matter of modelling is a mistake, and implies that fishers currently operating in an area would have little say in whether their fishing grounds will close.

Ensuring fishers buy into a new MPA is crucial for its success. Sutipond Somnam/Shutterstock

Ensuring fishers buy into a new MPA is crucial for its success. Sutipond Somnam/Shutterstock

But this study is valuable. It provides further evidence for how MPAs can serve as important tools to conserve marine habitats, manage fisheries sustainably and make food supplies more secure. It’s important to stress the political challenges of implementing them, but most scientists agree that more MPAs are needed. Some scientists are pushing to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030.

As evidence of the benefits of MPAs continues to emerge, the people and organisations governing them at local, national and international scales need to learn and evolve. If we can start implementing some highly protected MPAs, we can gather more evidence of their spillover benefits. This could convince more fishers of their vital role in boosting catches, as well as keeping people fed and restoring ocean ecosystems.![]()

Peter JS Jones, Reader in Environmental Governance, UCL and Rick Stafford, Professor of Marine Biology and Conservation, Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.