Coronavirus one year on: two countries that got it right, and three that got it wrong

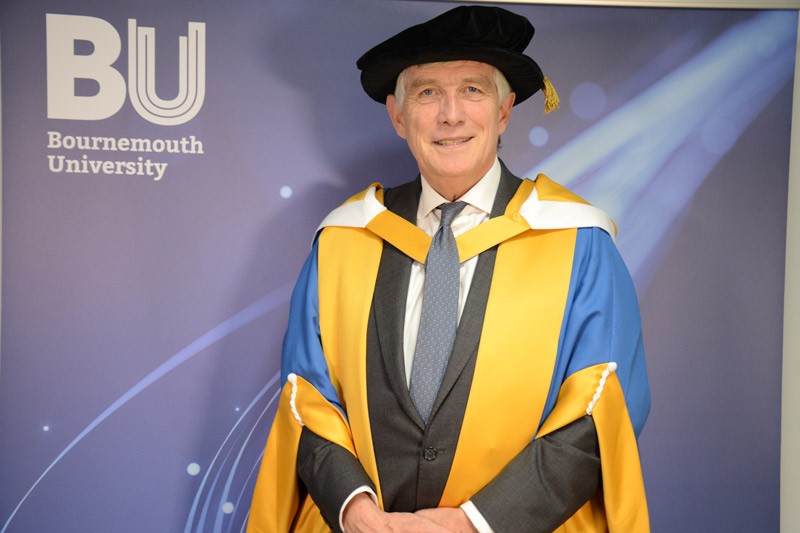

Darren Lilleker, Bournemouth University

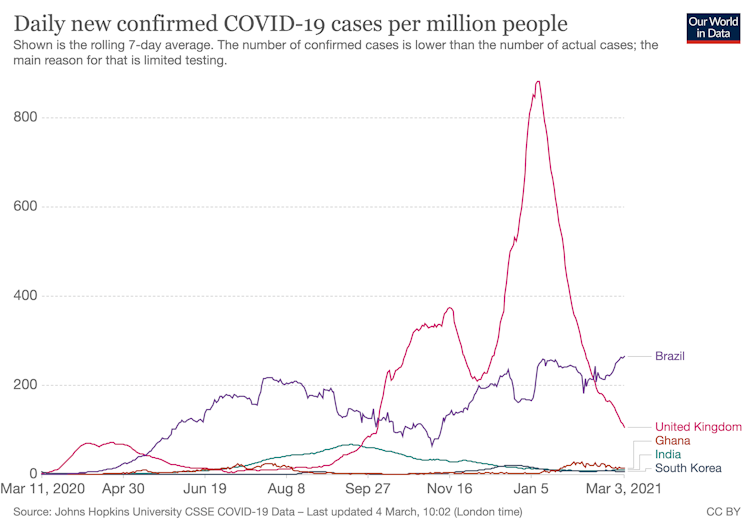

On March 11 2020, the World Health Organization declared that the COVID-19 public health emergency had become a pandemic: 114 countries were affected, there were 121,500 confirmed cases and more than 4,000 people had succumbed to the virus.

One year on, we have now seen 115 million confirmed cases globally and more than 2.5 million deaths from COVID-19.

“Pandemic is not a word to use lightly or carelessly,” said the Director-General of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus on that day in 2020. But in the year since that announcement, the fates of many countries have depended on how leaders have chosen their words.

The impact of the pandemic was unprecedented and all governments faced challenges dealing with a severe but highly unpredictable threat to the lives of their citizens. And some governments responded better than others.

My colleagues and I recently carried out a comparative study of how 27 countries responded to the emergence of the virus and first wave, and how they communicated that response to their citizens.

We invited national experts to analyse their government’s communication style, the flow of information on coronavirus and the actions taken by civil society, mapping these responses onto the numbers of cases and deaths in the country in question. Our work reveals contrasting responses that reflect a nation’s internal politics, suggesting that a government’s handling of the pandemic was embedded in existing patterns of leadership.

Read more of our coverage of the first anniversary of the pandemic:

COVID-19: how to deal with a year of accumulated burnout from working at home

Pandemic babies: how COVID-19 has affected child development

With news of the spread of COVID-19 flowing across international borders, domestic preventative measures needed to be explained carefully. The WHO proved ill-equipped, provided equivocal and flawed advice regarding international travel, even from Hubei province, and equivocated on the efficacy of wearing masks. So much came down to how individual leaders communicated with their citizens about the risks they faced.

Experts in crisis management and social psychologists emphasise the importance of clarity and empathy in communicating during a health emergency.

So who did well and who missed the mark?

South Korea and Ghana

We found two major examples of this style of communication working well in practice. South Korea avoided a lockdown due to clearly communicating the threat of COVID-19 as early as January, encouraging the wearing of masks (which were common previously within the nation in response to an earlier Sars epidemic) and quickly rolling out a contact-tracing app.

Each change in official alert level, accompanied by new advice regarding social contact, was carefully communicated by Jung Eun-Kyung, the head of the country’s Centre for Disease Control, who used changes in her own life to demonstrate how new guidance should work in practice.

The transparency of this approach was echoed in the communication style of the Ghanaian president, Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo.

Akufo-Addo took responsibility for coronavirus policy and explained carefully each measure required, being honest about the challenges the nation faced. Simple demonstrations of empathy earned him acclaim within his nation and also around the world.

“We know how to bring the economy back to life. What we don’t know is how to bring people back to life,” he famously said.

Brazil, the UK and India

South Korea and Ghana adopted a consistent tone highlighting the risks of the new pandemic and how they could be mitigated. Nations that fared less well encouraged complacency and gave out inconsistent messages about the threat of COVID-19.

In March 2020, just three weeks prior to placing the country under lockdown and catching COVID-19 himself, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson downplayed the threat, and said he had been shaking hands with infected people, against the recommendations of his expert advisers. Today, the UK has one of the highest per capita death rates from COVID in the world.

Avoiding a full initial lockdown, Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro – who also contracted COVID-19 – called for normality to continue, challenging expert guidance and polarising opinion along partisan lines. Such practices led Brazilians to mistrust the official information and spread of misinformation, while adhering to containment measures became an ideological, rather than a public health, question.

Meanwhile, Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, announced a snap lockdown with just four hours notice, which caused an internal migration crisis, with poor labourers leaving cities to walk hundreds or thousands of miles to their rural homes. Understandably, the labourers prioritised their fears of homelessness and starvation over the risk of spreading COVID-19 around the country.

None of these responses effectively considered the impact that coronavirus would have on society, or that credibility is earned through consistency. The poor outcomes in each case are a partial reflection of these leadership mistakes.

Bad luck or bad judgement?

Of course, the unfolding of the pandemic was not solely down to good or bad communication from leaders. Health systems and demographics may also have played a role, and the worst impacted nations not only had strategic weaknesses but are also global transport hubs and popular destinations – London, New York, Paris and so on. With hindsight, closing borders would have been wise, despite the contrary advice from the World Health Organization.

Still, it’s evident that leaders who adopted clear, early, expert-led, coherent and empathic guidance fared well in terms of their standing with the public and were able to mitigate the worst effects of the virus.

On the other hand, those who politicised the virus, exhibited unrestrained optimism or took to last-minute decision-making oversaw some of the nations with the most cases and deaths.

![]()

Darren Lilleker, Professor of Political Communication, Bournemouth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.