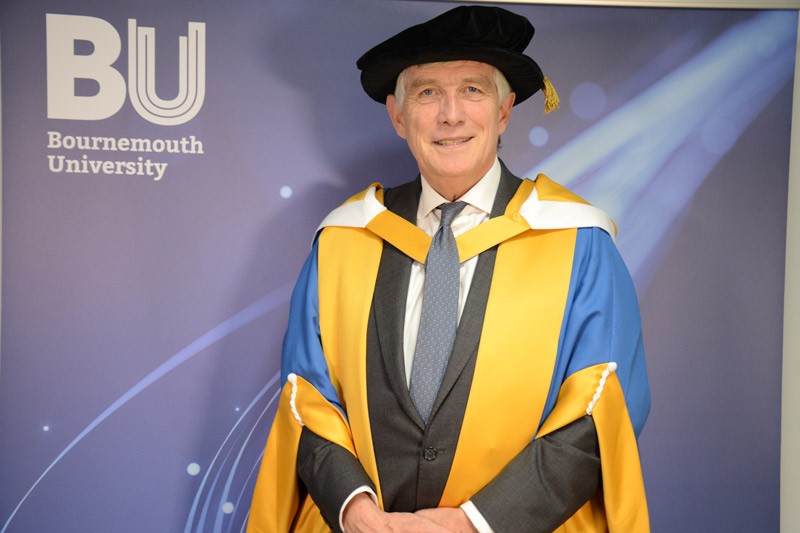

Keith Parry, Bournemouth University; Emma Kavanagh, Bournemouth University, and Eric Anderson, University of Winchester

Olympism, the 19th-century philosophy of the modern Olympic Games, can be summed up as making the world better through sport. At its heart lie three values: excellence, friendship and respect. While encouraging people to be the best they can be is an obvious feature, friendship is touted as “unique” to the Olympics compared to other sporting events.

Previous Olympics have seen athletes from diverse nations joining together in a spirit of celebration and camaraderie. Tales of Olympic Village festivities are usually the norm.

Tokyo 2020 is unlikely to afford participants the same experience. As Thomas Bach, the president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), has put it, this will be “the most restrictive sporting event in the world”.

As sporting events during the pandemic have included few or no spectators, televised sport has increased. But the entertainment value of these competitions should not obscure the perspective of the athletes themselves. The significant disruptions to their mental health and performance due to Covid-19 restrictions is well documented.

Athletes as people

Athletes, the IOC states, are “the central actors” in the Olympic Games. “They are the role models who inspire millions of children around the world to participate in sport and reflect the Olympic ideals.”

The decision to press ahead with the Games despite rising cases in Japan and beyond has put athletes in a difficult position. Morally they may even question whether they should take part, when over 80% of the Japanese public are not in favour of the Games taking place.

Competing in an Olympiad is often the high point in an athlete’s career, something that they have dreamed about and worked towards for all of their life. These dreams would see them celebrating with teammates as friends and family watch on.

Athletes also speak of “doing it for the fans”. Yet, Tokyo’s current state of emergency has seen spectators banned entirely.

Research has shown that empty stadiums can impact performance in some sports, particularly for athletes from host nations. It remains to be seen whether Olympians will value their experience competing in front of empty stands and whether the eyes of the world through television broadcasting will afford the same connection.

Read more: To watch or not to watch? The Tokyo Games raises difficult questions for fans

New anxieties

Bach has promised that the Tokyo Games will be “safe and secure”. But the dominant and highly transmissible delta variant is seeing higher hospital admission rates.

A cluster of Covid-19 cases at a Japanese hotel hosting members of the Brazilian Olympic team in mid-July 2021 highlighted the risks to participants. Members of Team GB, too, were forced to isolate after coming into contact with someone with Covid-19 on their flight to Tokyo. As of July 21, 91 Covid-19 cases linked to the Olympics had been recorded, with numbers rising daily.

Anyone flaunting strict Covid-19 rules (including quarantine on arrival and frequent testing) could face deportation. Such measures, while essential, are in marked contrast to the environment athletes will have experienced at previous games.

National Olympic committees have attempted to minimise the level of risk to athletes with Covid-19 vaccines. Some, however, have refused on the grounds that potential side-effects might impact on their training programmes.

As athletes have tested positive or come into contact with others who are, even while in supposedly secure environments, some nations are now withdrawing from major sporting events due to concerns over “player welfare and safety”. These decisions have, in turn, been criticised as hasty or made without consulting the concerned athletes. This demonstrates the complexity posed by Covid-19 and its effect on the freedom of athletes to choose whether to compete or not.

Part of being an elite athlete, of course, is the ability to respond to adverse circumstances. Success is often linked to the ability to negotiate and overcome challenges. These are nonetheless unprecedented fears for athletes and sources of new anxieties.

Bubble Life

Elite sport is already a highly pressurised and stressful environment. Living in the secure biosafe bubbles, that have become the new normal at events around the world, has proven to be an additional stress and detrimental to athletes’ mental health.

Read more: Coronavirus: why self-isolation brings mental health strain for elite athletes

Athlete mental health and welfare is increasingly being recognised as key to performance. Some national sporting bodies are providing specialist support to athletes during Tokyo 2020.

Team GB has been recognised as leading the way in prioritising mental health, putting in place a support team of psychologists and specialists. The British Athletes Commission has also put in place a 24-hour hotline for athletes to report and manage the impact of any abuse they may recieve during the games. However, such services certainly will not be available to every nation’s team.

Read more: Adoration and abuse: how virtual maltreatment harms athletes

For Australian basketball player Liz Cambage, the thought of a bubble Olympics, without the support of family, friends and fans was “terrifying”. She subsequently withdrew from the Games.

Team USA Paralympic swimmer Becca Meyers, meanwhile, has withdrawn from the Paralympic Games due to restrictions that prevent her own carer from accompanying her. Tokyo would have been her third Olympiad. This shows that, clearly, Covid-19 restrictions are not providing an equitable or safe games for all athletes.

The athletes competing in Tokyo have taken five years to get there. They now aspire to perform while navigating not only established performance-related stresses, but also new anxieties. Medals in 2021 have the potential to be won or lost by those who can best manage the demands of competing during a global pandemic.

Keith Parry, Deputy Head Of Department in Department of Sport & Events Management, Bournemouth University; Emma Kavanagh, Senior Lecturer in Sports Psychology and Coaching Sciences, Bournemouth University, and Eric Anderson, Professor of Masculinities, Sexualities and Sport, University of Winchester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.