A new paper has been published in the BMJ, providing advice for health workers on identifying signs of reproductive coercion – when a woman becomes pregnant, or has pregnancy forcibly prevented or terminated, against her wishes.

Reproductive coercion can involve a range of behaviours, all of which are forms of abuse. It can include a partner or family member using psychological pressure and emotional blackmail, as well as physical and sexual violence, to dictate a woman’s reproductive choices. As with all forms of abuse, many authorities can be involved, including social workers and the police. Healthcare workers are often well placed to spot the signs first.

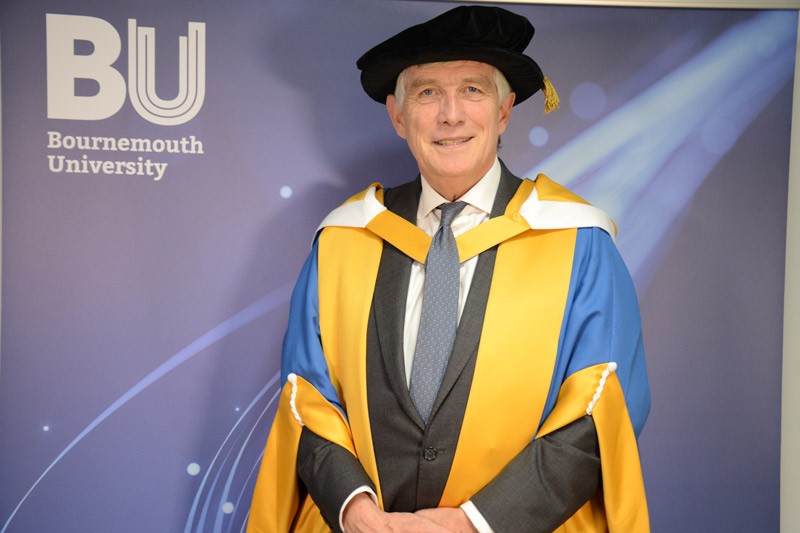

“Although this has been known to happen for a long time, it is only in the last decade that the extent of reproductive coercion has been studied,” said Professor Sam Rowlands of Bournemouth University who led the group producing the new educational paper. He was also one of the first health professionals to write on the subject.

“More information and guidance are still needed to help clinicians recognise and support the women affected,” he added.

Throughout his studies, Professor Rowlands has found that women can be reluctant to disclose whether their pregnancy, or termination of a pregnancy, was forced upon them. This can be because there may be children involved or because they feel dependent upon their dominant and controlling partner.

“It is easy to completely miss the signs as they can be invisible from the outside, so this often hides in plain sight,” explained Professor Rowlands.

In this new paper, Professor Rowlands and his team advise that repeated requests for emergency contraception, pregnancy testing, sexually transmitted infection testing, or termination of pregnancy could be signs that coercion is taking place. Women experiencing reproductive coercion are also more likely to request highly effective contraceptive methods such as implants, intrauterine contraceptives, or sterilisation.

They also set out a series of questions that clinicians can ask women to gather more information if they suspect coercion is happening. This includes how to ask the woman’s partner to leave the room so they can speak to her on her own, without arousing suspicion.

“It’s important that doctors’ questions are specific and make it clear to the women affected that they understand,” explained Professor Rowlands. “Vague questions such as ‘how are things at home?’ and questions that come across as routine box-ticking are very unlikely to lead to someone confirming they have been subjected to abuse,” he continued.

The study team advise that a professional relationship between doctor and patient, based on trust and confidentiality is critical. Women experiencing this form of abuse will know the ramifications of disclosure, for example the doctors may be duty bound to get the police and other authorities involved. This can be another barrier to opening up. In these cases, they advise that doctors can give cards to the women explaining how they can get advice and support. Posters on the walls of clinics can also help raise awareness amongst people subjected to abuse, or to people who suspect a friend or family member may be affected.

The paper concludes with practical steps that doctors can take if a woman subjected to this abuse feels unable to break away from their partners.

“As professionals, we can help women by supplying concealable contraceptives, so they are able to offer up some kind of resistance to the coercion,” said Professor Rowlands. “It is good for the patients to have a doctor who understands what is going on but that they trust enough to know they will not routinely get other parties involved against their wishes.

"A combination of providing them with contraception that their partners are unlikely to discover and information about how to get support is a positive way to empower women to make the decision on the next steps when they feel the time is right,” he concluded.

The education paper can be found on the BMJ website.