The iron age lady was found lying on carefully arranged animal bones.

The iron age lady was found lying on carefully arranged animal bones. Archaeologists have uncovered new information about the life and death of a young Iron Age woman in Dorset who they believe could have been murdered as a human sacrifice.

By investigating the more than 2000-year-old cold case, the Bournemouth University team have also been able learn more about what life was like for people at the bottom of the social hierarchy at the time.

Their analysis suggests she was in her late twenties when she died and had lived a physically demanding and hardworking life. They also found that she suffered damage to one of her ribs, possibly inflicted through violence, weeks before she was killed by a stab wound to her neck.

The combination of factors in their study suggest that this is rare physical evidence that human sacrifice took place in Iron Age Britain.

The findings have been published in the Antiquities Journal.

Students have been excavating prehistoric settlements in Winterborne Kingston in Dorset for fifteen years

Students have been excavating prehistoric settlements in Winterborne Kingston in Dorset for fifteen yearsStudents and staff from Bournemouth University have been excavating the site of Winterborne Kingston in central Dorset for over fifteen years since they first discovered prehistoric settlements in the area.

Whilst they have previously uncovered the remains of humans buried in graves and storage pits, this appears very different.

“In the other burials we have found, the deceased people appear to have been carefully positioned in the pit and treated with respect, but this poor woman hasn’t,” explained Dr Martin Smith, Associate Professor in Forensic and Biological Anthropology at Bournemouth University.

“We have also previously found ceramic pots and remains of joints of meat next to human remains, which we believe are offerings for the afterlife. This was nothing like that. The young woman was found lying face down on top of a strange, deliberately constructed crescent shaped arrangement of animal bone at the bottom of a pit, so it looks like she was killed as part of an offering,” he added.

By studying the bones, the archaeologists have been able to discover more information about the victim’s life and tell some of her story.

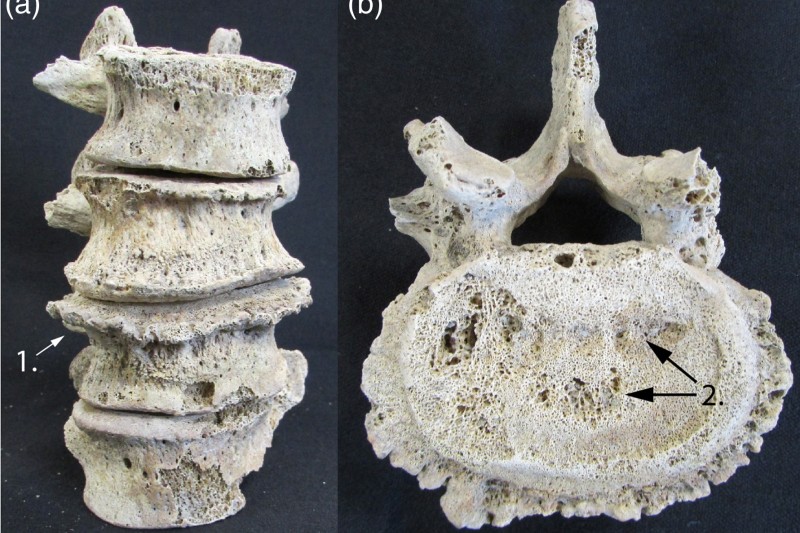

Degeneration of the spine suggests a rigorous and hard working life

Degeneration of the spine suggests a rigorous and hard working life Her spine showed signs of significant degeneration and arthritic change for her young age, and she also had damage to some of the discs between her vertebrae. This indicates exertion from regular hard work.

She also had well developed and rugged muscle attachments which is another sign of a rigorous and continuous physical activity.

The team also studied the isotopes in her teeth, which means they can identify where someone got their drinking water from as their teeth were developing as a child. This suggested that she originated from over twenty miles from the settlement. They are now carrying out DNA analysis to establish whether she was brought to the settlement as an outsider from another community.

“All the significant facts we have found such as the problems with her spine, her tough working life, the major injury to her rib, the fact she could have come from elsewhere, and the way she was buried could be explained away in isolation,” Dr Smith said.

“But when you put them all together with her deposition face down on a platform of animal bone, the most plausible conclusion is that she has been the victim of a ritual killing. And of course, we found a large cut mark on her neck which could be the smoking gun,” he added.

The team highlight that as well as providing evidence of human sacrifice, being able to understand the life of the Iron Age woman has been important, both in terms of telling her individual story but also in understanding more about less-fortunate members of society in the past.

“The burials that get the most attention tend to be those of higher status, privileged people,” Dr Smith explained. “However, being able to humanise the story of this woman’s life has given us a valuable glimpse into the other side of Iron Age society. Behind every ancient burial we find is someone's story waiting to be told.”