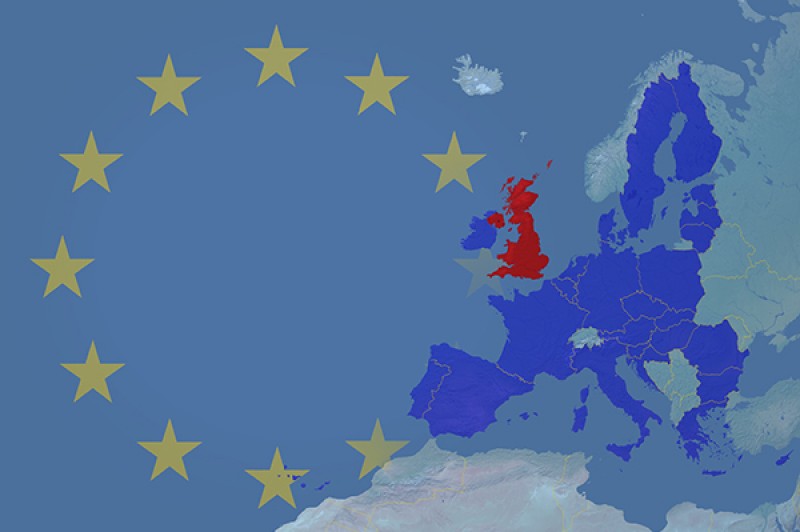

As I write this, we are facing an uncertain future. The political shenanigans relating to the UK leaving the European Union would be amusing, were not the whole situation so important. This is particularly the case from the perspective of food and farming. As with Brexit, our food futures depend on the individual: there are no excuses; ultimately we get what we ask for.

Historically our farmers have been very successful at producing the food that they have been asked to produce. Farmers, and the whole population, were encouraged to “dig for victory” during the Second World War. Farmers also responded to post-war demands and by the 1970s we had one of the most effective and efficient agricultural systems in the world, some of the most advanced agricultural and food research, and the best agricultural advisory service. All this was to change. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the agricultural policy of successive UK governments have created a system of food supply that is inherently vulnerable and unsustainable. UK governments also decimated our research and advisory base.

The CAP (article 39) has very laudable aims; to increase agricultural productivity, to ensure a fair standard of living fragrance community, to stabilise markets, to ensure supplies, and to ensure that supplies reach consumers at reasonable prices. Farmers were very successful in achieving these aims, but individuals will play to the rules that are put before them, with the result that European agriculture over produced, and produced using systems that were inherently damaging to the environment. The food supply chains that link farmers to consumers have, at the same time, becoming globalised, complex, opaque and dominated by powerful processors and retailers. However much these powerful corporations might ask us to trust them, it is difficult.

But what of the future? We are currently at a very important point in time, regardless of Brexit global problems with regard to the secure availability of good quality food, global warming and other aspects to the damage that we have done to our environment, mean that we must address these issues and the way they impact upon our food supply, if our children and grandchildren are to have good quality food to eat.

Brexit poses specific concerns, in that it is more than likely the UK will sacrifice the high quality food and environmental standards that it does have (and though open to criticism they are still much better than much of the world) in order to obtain trade deals in other areas. It is quite possible that we will end up scouring the world’s dustbins for food if we do not place the quality of food that we consume and the environment within which it is produced at the forefront of our thinking.

Economists have indicated that food is not a public good but a private good. Only an economist could justify this sort of distinction. At the start of the 21st century everyone should have access to good quality food. The right to feed oneself in dignity, the right to adequate food, is a long-standing international human right set out by the United Nations. The fact that many people in the 21st century UK, the fourth largest economy in the world, do not have access to good quality food is an indictment of ourselves as ultimately this is a collective choice of us as individuals.

The fact that our environment has been nationally and internationally degraded by agriculture is equally sad; we have taken out an overdraft with the environment and we are going to have difficulties paying it back. We should not direct our anger at the farmers or the food companies; they only do what we ask them to and what we let them do. We decide what policies to have through our elected members in parliament. We also decide what food goes in our mouths, as a result of what we choose to purchase. The decision about our food futures is ours. If I asked to put my fingers in your mouth you would call a police officer, yet every day we put things in our mouths without a second thought.

Dr Sean Beer, Senior Lecturer in Agriculture