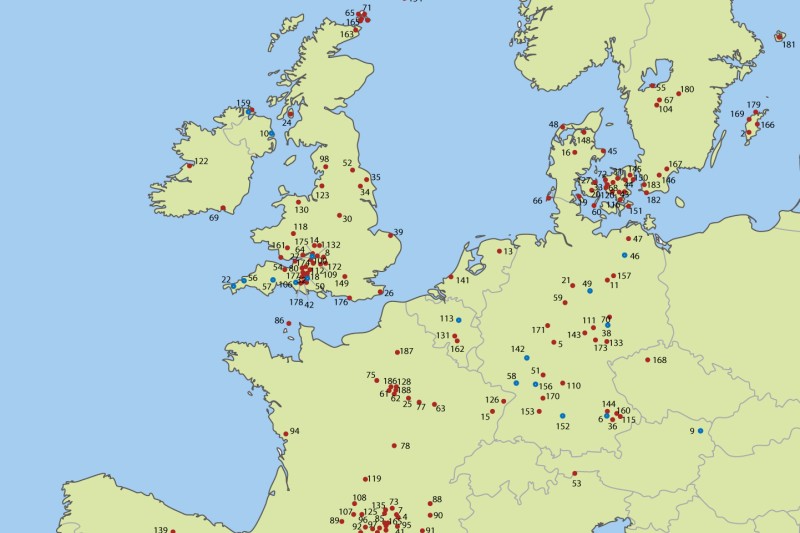

Map of Northwestern Europe showing archaeological sites with violence-related injuries in Neolithic skeletal remains (red) and settlements/enclosures/mass fatality sites with evidence for collective violence (blue).

Map of Northwestern Europe showing archaeological sites with violence-related injuries in Neolithic skeletal remains (red) and settlements/enclosures/mass fatality sites with evidence for collective violence (blue). Violence and warfare were widespread in many Neolithic communities across Northwest Europe, a period associated with the adoption of farming, new research suggests.

Of the skeletal remains of more than 2300 early farmers from 180 sites dating from around 8000 – 4000 years ago, more than one in ten displayed weapon injuries, archaeologists found.

Contrary to the view that the Neolithic era was marked by peaceful cooperation, the team of international researchers say that in some regions the period from 6000BC to 2000BC may be a high point in conflict and violence with the destruction of entire communities.

The findings also suggest the rise of growing crops and herding animals as a way of life, replacing hunting and gathering, may have laid the foundations for formalised warfare.

Researchers used bioarchaeological techniques to study human skeletal remains from sites in Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Spain and Sweden.

The team collated the findings to map, for the first time, evidence of violence across Neolithic Northwestern Europe, which has the greatest concentration of excavated Neolithic sites in the world,

The team from the University of Edinburgh, Bournemouth University, Lund University (Sweden), and the OsteoArchaeological Research Centre in Germany examined the remains for evidence of injuries caused predominantly by blunt force to the skull.

More than ten per cent showed damage potentially caused by frequent blows to the head by blunt instruments or stone axes. Several examples of penetrative injuries, thought to be from arrows, were also found.

Some of the injuries were linked to mass burials, which could suggest the destruction of entire communities, the researchers say.

Dr Martin Smith, Associate Professor in Forensic and Biological Anthropology at Bournemouth University, said: “The study raises the question to why violence seems to have been so prevalent during this period. The most plausible explanation may be that the economic base of society had changed. With farming came inequality and those who fared less successfully appear at times to have engaged in raiding and collective violence as an alternative strategy for success, with the results now increasingly being recognised archaeologically.”

Dr Linda Fibiger, of the University of Edinburgh’s School of History, Classics and Archaeology, said: “Human bones are the most direct and least biased form of evidence for past hostilities and our abilities to distinguish between fatal injuries as opposed to post-mortem breakage have improved drastically in recent years, in addition to differentiating accidental injuries from weapon based assaults.”

The study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.